Neuroscientists reckon that the negative impact of Covid-19 stress on our mental health is greater overall than the virus itself. Keiron Sparrowhawk considers the cognitive domains that have the greatest impact on leaders during these testing times

What makes a good leader? It’s a question that has been discussed and analysed in thousands of books, millions of conferences and academic lectures. A reasonable definition is the ability to ensure good outcomes even when under stress.

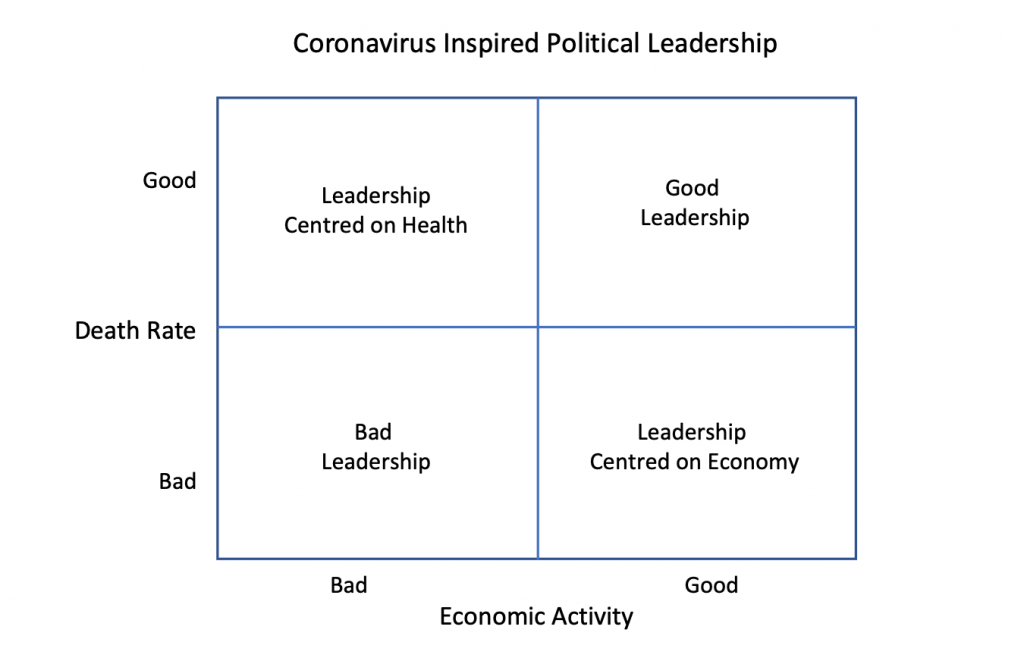

In the current coronavirus context, we could consider whether the global political leadership is providing protection to their citizens and their economies under the stress of the pandemic.

From an objective perspective, the coronavirus is a perfect, global leadership test, as it treats everyone the same. It simply exists to wreak havoc among the most vulnerable. If we accept this premise, it gives us a unique opportunity to compare leadership on a global basis using the simple 2×2 basic matrix below.

From the outcomes, we can see how good the leader is. Having dealt with the global politicians, what does the stress of the coronavirus pandemic say of your leadership?

Stress is a well-used, but not well understood noun. For example, not all stress is bad. Without it we wouldn’t develop to our full physical or mental potential and become good leaders. However, stress can also destroy us. It can undermine our productivity, create bad behaviours, and it is a cause and significant component of mental illness. Neuroscientists reckon that the negative impact of coronavirus stress on our mental health is greater overall than the death rates. Let’s take a closer look at stress.

The impact of stress

Unrestricted stress ‘ignites’ areas of the brain, causing inflammation, in some cases destroying the neuronal pathways that manage your behaviour and emotions. It does this through inflammatory cytokines, such as Interleukin-6 (IL-6), which are substances secreted by the immune system in response to stress.

When regulated, IL-6 recycles dead or dying cells, ensuring you can re-use the proteins in them. Unregulated, IL-6 will attack areas of weakness, including the neuronal pathways that control your behaviour and emotions when undertaking a challenge or when responding to stress. Under stress we may perform badly, get angry or easily upset, or behave inappropriately. If prolonged, the brain damaged by stress increases our risk of mental illness.

To counter the effects of IL-6 and regulate it, your body produces the hormone, Cortisol, which has an anti-inflammatory action. Cortisol puts out the ‘fires’ ignited by IL-6 and protects neuronal pathways, preventing brain damage.

However, even Cortisol has its limits and the continued stresses associated with the pandemic lockdown could overcome it. It would be an advantage if we could directly regulate the action of Cortisol, but efforts to do this, including drugs, have failed. However, the long-term anti-inflammatory action of Cortisol can be modified depending on the health of your cognition. A strong, healthy cognition gives Cortisol durability and enables it to be more effective in extinguishing the fires ignited by IL-6, even if stress is exerted over a longer period of time or it’s severity increases.

Thus, it is your cognition that empowers you to remain in a calm, anti-inflammatory state, maintaining good behaviour, performance and mental health. Your cognition consists of five core domains, each of which controls specific abilities. These are: working memory – to make decisions; episodic memory – to recall; attention – to focus and concentrate; processing speed – to act with speed and accuracy; and executive function – to plan and organise, be creative, and emotionally self-regulate. The good working of all five domains are critical for your leadership. The stronger your cognitive domains, the greater your control of Cortisol and its regulation of IL-6. Let’s consider two cognitive domains in depth to see how they can support or undermine your leadership.

The cognitive domains

Episodic memory is your ability to recall past events that are relevant to the current context, so that you can use your experience (wisdom) to help you through new tasks or situations. Rather than starting the new task at the bottom, your episodic memory allows you to get up the learning curve. You are also able to impart this knowledge to others. Deep structural, thinkers are great for recalling past experiences and learning from them. However, if that deep thinking goes awry, instead of learning from the experience, you ruminate over bad memories, and potentially become depressed, with the deeper your thinking, the deeper your depression.

Executive function is another cognitive domain that gives you the ability to plan and organise, to be creative and to control your emotions. In a good state, it allows you to use your creativity to plan different ways to undertake a task or challenge. That way, if one of your plans hits trouble, you don’t get upset or angry because you have contingencies to fall back on. Indeed, you may even try out the alternatives to see if they give a better outcome than your first thinking. But in a poor state you catastrophise. Thinking forward all you see is mayhem and disaster and thus you stay put, as though stuck in a rut. This condition causes anxiety.

You can see that episodic memory and executive function are directly connected to leadership qualities, but that both can fail predisposing us to mental illness despair. Getting the balance in favour of healthy cognition is critical. Whereas, you can’t regulate Cortisol directly, you can monitor and enhance your cognition and control Cortisol indirectly. There are many ways to do this, including the adoption of healthy habits. It’s intuitive that to be an effective leader, you should follow healthy habits. This is clearly the case with your physical health, but we now have a much clearer connection to your cognitive health, too.

The brain develops habits in response to a ‘cue’, a prompt. For example, if you feel bored (the cue), a bad habit could be to reach for… an unhealthy snack, alcohol, non-prescription drugs or excessive web surfing.

The outcome of this bad habit may overcome the boredom. You get a ‘reward,’ but the instant gratification obtained does harm in the long-term, even to your leadership. You need to replace bad habits and this requires acceptance by you that the habit is bad, and planning to replace it.

Addressing boredom

Once you accept you have a bad habit, recognise the cue that prompts it. It could be boredom as above, but it could also be a stressful environment or situation, and so on. Second, plan the adoption of a healthy habit to replace it. Then, when you recognise the cue, instead of reaching for the bad habit, you have an alternative instead. For example, in response to feeling bored, you could:

1Undertake simple exercises or activities; e.g., a walk, run or cycle, or reading a good book, gardening, decorating, cleaning the house.

2Consume healthy foods; instead of sugary snacks, try vegetables (carrots), whole fruits, fish.

3Better hydration; replace alcohol, caffeine or sugar-loaded fruit juices with fresh water instead.

4Achieve good quality sleep; plan for a good night’s sleep to recover from a busy day.

5Keep good social interactions; spend time with people who will help you start and keep these good habits. These simple habits overtime will strengthen your leadership.

If adopting a good habit seems daunting, then you could initially try cognitive training. Cognitive training gets your cognition into a better state from where you will have more success adopting the new habit. Advances in neuroscience and technology are casting light on how the brain works and how you respond to stress. These advances can help you to lead a healthier, happier, more productive life, and will enhance your leadership, too.

One final consideration

We looked at the indirect impact of the coronavirus pandemic, but what about the body’s reaction to the infection itself? In the most serious infections the virus gets deep in the lungs. The body responds by releasing large amounts of IL-6 into the lungs, destroying the cells to prevent the virus from replicating. However, this ‘storm’ can cause death, as the infected patient dies by drowning in the liquids released from their dead lung cells. This is Covid-19 induced pneumonia.

Those who survive have high levels of circulating IL-6, which can cause damage to the other organs, including the brain. These people are in need of help, including cognitive scanning and strengthening programmes. It’s doubtful many will get this, but perhaps we will learn from this experience and ensure such programmes are available for future pandemics.

Kieron Sparrowhawk is the founder of MyCognition an award-winning, R&D science-based company dedicated to understanding and improving cognitive fitness. They research, develop and create products that measure and enhance cognitive fitness in personal wellbeing, education, business and healthcare sectors. They have received NHS and ORCHA approval, a prestigious award from UCL for their research and have completed over 20 clinical and real-world studies. For more information visit www.mycognition.com or email Martina@mycognition.com